|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Neither rain nor wind nor rust…

“The towers are designed not to rust, but within a few weeks of this one being installed in 2021, rust was visible,” David Lumpkin, ecologist, reflects.

The 30-foot Motus tower he’s describing is a sentinel on a remote, exposed hill at Toms Point on the northern edge of Tomales Bay. The tower is barraged by wind and bathed in salty fog — a recipe for disrepair for the steel and aluminum components keeping the structure aloft.

For the past five years, Lumpkin, who is based at Cypress Grove Preserve, has overseen the maintenance of all four All Hands Ecology Motus towers. Even as the rust takes root, these towers are standing the test of time.

A day in the life of Motus maintenance

On a cloudy summer day, Lumpkin hikes a mile uphill from his truck to the Motus tower at Toms Point to update the computer operating system. It’s a familiar route. Lumpkin checks on this tower periodically, especially after the most violent of storms whip through with 60 to 70 mile per hour winds and heavy rains.

On this near-windless day, Lumpkin opens the sensor box at the tower. Two Pacific tree frogs move to the edge of the door on the inside of the box, which is waterproof but clearly not frog-proof. Other towers in Lumpkin’s care have uninvited inhabitants — yellow jackets and mice have been found nesting in battery packs — not ideal for the hardware.

Lumpkin plugs his laptop into the maze of cables, patching his computer into the SensorStation, the hardware that will pass along data to the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, a network of over 2,000 receiver towers, in 34 countries — an ever-evolving database of detections from more than 50,000 tagged animals.

A game changer for research

As he updates the computer, Lumpkin reflects on All Hands Ecology’s long-term research of Dunlin, the small, numerous shorebirds on Tomales Bay.

“Dunlin declined by more than three-quarters in the three decades that we were tracking their numbers.” explains Lumpkin. “Motus provides a lot more context in terms of how the Dunlin are behaving and why our numbers might be dropping.”

Lumpkin shares that before the introduction of solar powered Motus tags, existing tags small enough to be carried by birds like Dunlin had to be battery powered and would only last a few months. Prior to Motus, tracking numbers of tagged Dunlin through their migratory route up to breeding ground in Alaska was highly impractical.

The game changing advancements in tag technology along with the rapidly expanding network of towers were “the motivation for installing Motus towers on our coastal preserves,” notes Lumpkin.

Cooperative buy in

“We’re shifting from focusing on our projects to supporting the network for other projects,” says Lumpkin.

Lumpkin explains that the tagging of Dunlin is complete, though the towers will continue detecting Dunlin over the next few winters. The towers are now proving their worth through supporting studies by other researchers and partners, such as Pacific Eco Logic’s study of brown pelican movement and San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory’s tracking of snowy plovers, a federally and state listed species. Lumpkin also highlights the USGS’s study of hoary bats with ground-breaking findings that could support the bat being listed as a species of “special concern.”

“Motus works because there’s a cooperative buy in,” Lumpkin points out. “The more organizations that support the system, the more useful it is to everyone.”

The promise of technology

The computer update to the Toms Point tower takes about 15 minutes. Soon Lumpkin will go to the Martin Griffin Preserve Motus tower to update its system, which has been acting “glitchy,” rebooting every six minutes.

Despite the hassles of the digital world, Lumpkin is excited about the future of Motus technology.

Lumpkin explains that the towers are modular, like an Erector Set. Pieces can be swapped out. When cables become infiltrated by rust or a connector corrodes from the damp, salty air, Lumpkin will replace them.

The towers can also be added to, which gives them the potential to integrate cutting edge technologies, such as Bluetooth. Western Monarch butterflies, whose numbers have plummeted, are being equipped with Bluetooth tags, weighing as little as a grain of rice. Partner organizations at Point Blue Conservation Science and the Xerces Society are using these tags with Motus towers to answer key questions about their movements and inform conservation measures.

In the future and with adequate funding, All Hands Ecology towers can be retrofitted to participate in these innovative technologies.

Room to grow

With the computer update of the Toms Point tower complete, Lumpkin packs up his gear and closes the sensor box. He gestures northward toward Dillon Beach, which appears as a cluster of houses on the edge of the gray water.

“The next tower on the coast isn’t until Humboldt County, over 200 miles away.” The distance between the towers is a “dead zone,” where a bird can easily disappear from tracking.

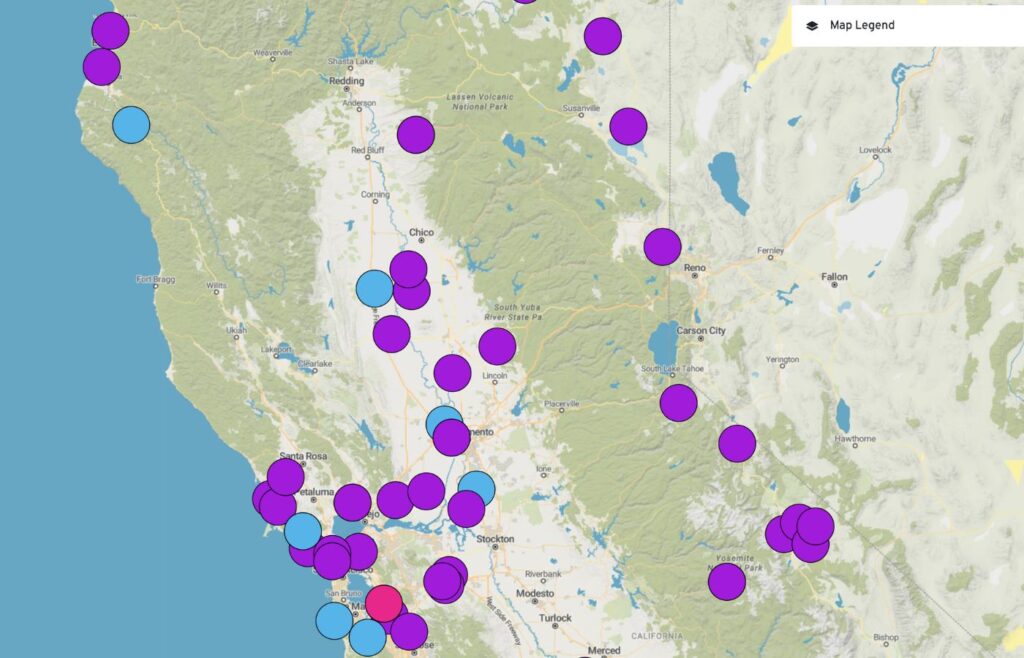

The Motus network in California has room to grow, in comparison to its East Coast counterparts. The success of Motus in informing conservation efforts locally and worldwide depends on the network of towers continuing to expand, as well as investments in tower upkeep and emerging technologies.

Be part of the Motus network

Support the future of Motus. The future of conservation research depends on donations and grants from generous individuals, businesses, foundations, and local community groups. Become a member or donate.