|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Roads shape the lives of mountain lions

When we think of roads and mountain lions, well-known stories come to mind, like that of Los Angeles’s P22. This adult male mountain lion navigated one of the most urbanized places in the country, reaching near celebrity status for his perilous freeway crossings and his role in inspiring the construction of a $92M wildlife crossing.

While the situation here in the North Bay is quite different, roads shape the lives of our local lions. At the Living with Lions project, we’re exploring these impacts through a new study and are partnering on another study to understand how mountain lions are “living with roads” and the challenges these apex predators face.

Living with roads

Mountain lions in the North Bay are “living with roads,” a term Dr. Quinton Martins, Living with Lions principal investigator coined. North Bay mountain lions live in a landscape distinct from much of the state. In the South Bay and southern California, dense human populations and road networks push lions into remaining intact habitat, creating pinch-point crossings. In contrast, far northern California and the Sierra Nevada have sparse development and strong habitat connectivity, so lions encounter roads less often.

The North Bay sits between these extremes, creating a uniquely complex setting for movement and coexistence. The human population and road networks are just sparse enough that much of the area can support mountain lions, yet development is dense enough that lions are guaranteed to encounter roads regularly.

“Like the name of the study ‘Living with Lions,’” explained Martins. “North Bay mountain lions are living in an area where they overlap with not only more people, but also more roads than any other population.”

A new study is connecting the dots

Martins and Scott Jennings, All Hands Ecology quantitative ecologist, are working to understand the connections between where lions cross roads and the characteristics of these roads and the habitat. Martins and Jennings looked at road crossing data from 22 GPS-collared mountain lions in Sonoma and Napa counties between 2016–2023.

“The study found obvious crossing hotspots where individual lions crossed almost once per month,” explained Jennings. “There were also many crossing warm spots, suggesting mountain lions often cross roads wherever they happen to encounter them in suitable habitat.”

Jennings found that both male and female mountain lions were more likely to cross roads where patches of forest and brush were more connected to each other. Another finding was that bridges and culverts are strongly related to road crossing locations — features which often are associated with creeks and vegetation.

“Most of the North Bay has good habitat connectivity crossed by local and rural roads,” explained Martins.

Martins explained further: “It may be that our cats have become habituated to roads — not seeing them as an obstacle, but as being part of their landscape.”

Along Highway 12, Jennings found hotspots that weren’t identified in previous connectivity plans. The study also pointed to sections of Arnold Drive in Glen Ellen, which runs parallel to Highway 12. These sections seem to be important for mountain lions where connectivity across Sonoma Valley may be limited.

After the research analysis is complete, a paper will be submitted for peer review and publication.

Two lions hit in Sonoma Valley

On October 3 of this year, an uncollared male mountain lion was hit by a vehicle on Arnold Drive in Glen Ellen. Though initially stunned, the animal was able to flee from the road. Six weeks later, P51, a recently collared, young mountain lion was fatally struck by a vehicle on Highway 12 opposite Oakmont Village in Kenwood.

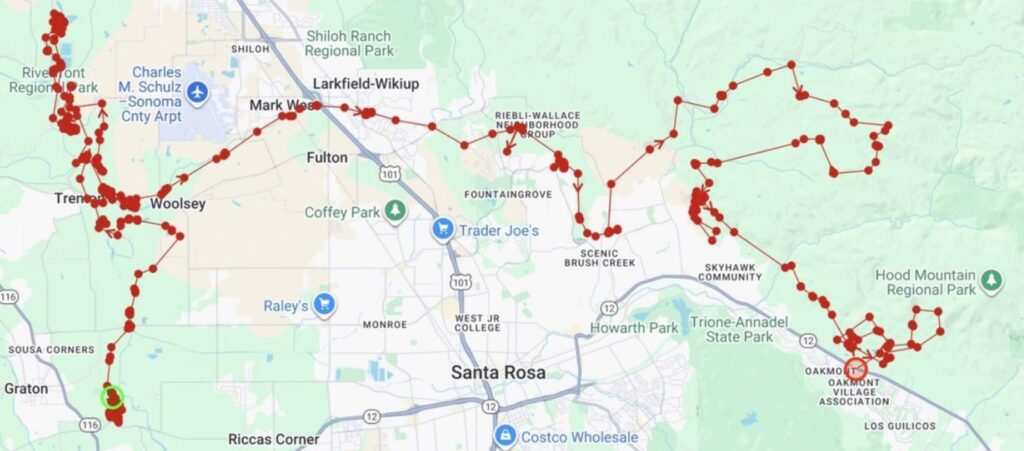

In the GPS tracking of P51, his bold trajectory revealed the crossing of country roads, traveling beneath a bridge on Highway 101, and moving through an urban area of Santa Rosa. With sufficient forest and brush as cover, he was able to make a 49-day journey from west Sonoma County, near Graton, to the Mayacamas Mountains and south to Sonoma Valley.

“For a dispersal mountain lion, who is moving away from his mother’s home range, chances of survival are always going to be low,” said Martins. “Threats include being injured or killed through fighting with a territorial adult, malnutrition, disease, and navigating a human-dominated landscape where risks due to depredation of livestock or being hit by a car are very real. This area [where P51 was hit] is not typical mountain lion habitat and there is no obvious vegetation corridor.”

Pinch points in Sonoma Valley

For these far-ranging animals, whose areas can extend more than 100 square miles for an adult male, there are pinch points, where crossing a road might involve the risk of vehicle collisions.

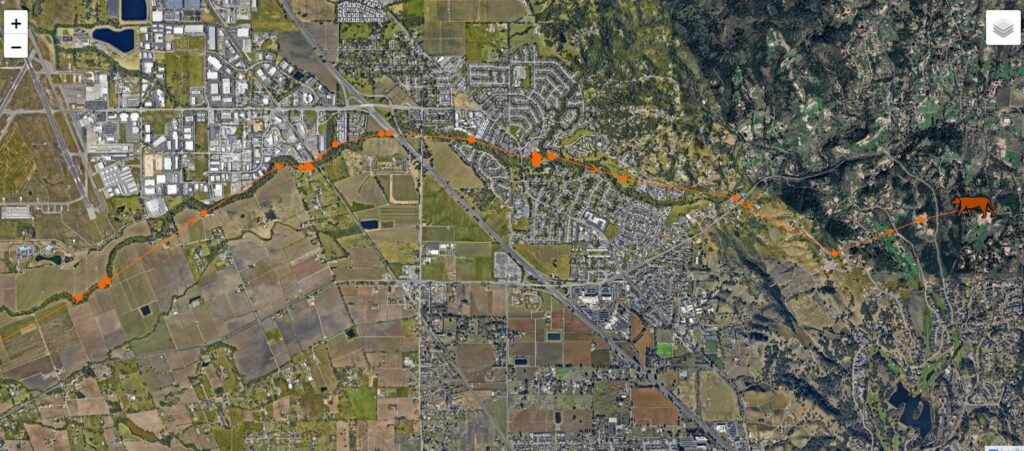

In 2022, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) identified a 13-mile stretch along Highway 12 between Los Alamos Drive and Agua Caliente Road in Sonoma Valley as one of California’s 61 high-priority wildlife barriers, prompting Caltrans and CDFW to reach out to local conservation groups in 2024 to collaborate on restoring connectivity. Partnerships between All Hands Ecology, Sonoma Land Trust, Caltrans, CDFW, and Pathways for Wildlife have launched the first phase of a major effort to improve wildlife passage — and reduce wildlife vehicle collisions along this part of the highway. Sonoma Land Trust has since funded a one-year study to gather essential baseline data to guide this work.

A collaborative study in Sonoma Valley

The Sonoma Land Trust study includes year-round monitoring of 36 bridges, culverts, and at-grade crossings using video, paired with 12 months of roadkill surveys on Highway 12 and a community science effort on nearby county roads. Researchers will also conduct landscape assessments, evaluate site-specific opportunities and constraints, and develop connectivity models for six locally occurring species. All findings will be synthesized into a comprehensive wildlife crossing infrastructure plan outlining recommended improvements — from new or retrofitted passages to directional fencing, jump-outs, maintenance strategies, and key land protection needs.

“Sonoma Valley is lucky to have so many good creeks and culverts,” says Chris Carlson, project lead and Sonoma Land Trust stewardship manager. “But they were built for water, not wildlife. We’re excited to take meaningful steps toward securing a future for these species.”

Stay aware and slow down

Martins has suggested that in the North Bay lessening the risks of car strikes can also be addressed through community outreach. “Encouraging drivers to reduce speed and helping people understand the specific types of areas where mountain lions and other wildlife are most likely to be on the roads are part of reducing the risks for lions,” shared Martins.

Keep up to date

Follow Living with Lions updates by subscribing to our eNews and following True Wild Conservation.

Studies like these help drive the future of conservation research and depend on donations and grants from generous individuals, businesses, foundations, and local community groups. Become a member or donate today.